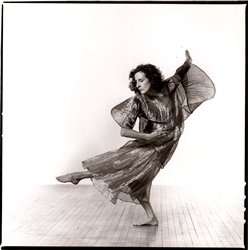

Trisha Brown: Choreographer, Innovator, Humanist, Dance/USA Honor Awardee

Editor’s note: On June 17, 2015, Trisha Brown received the Dance/USA Honor Award for “her extraordinary leadership in the dance field through artistic excellence and/or force of vision.” On March 18, 2017, the dance world lost this visionary, known and admired for her intellect, her artistry, and her boundary-pushing vision. Brown was 80. From the Green Room shares this article from June 9, 2015, written on the occasion of Brown’s Honor Award.

By Wendy Perron

Trisha Brown is becoming more sacred to us every year. Not only is she a great artist who pushed the boundaries of contemporary dance, but she is also a fine human being, an example of compassionate leadership. While dance legends like Martha Graham and Jerome Robbins were notoriously “difficult” to the point of occasional cruelty, Trisha was always respectful, nurturing and generous. She fulfills the promise of a new, feminist way of being an artistic director.

Having danced with Trisha in the 1970s, when the company was just five women, and having followed her choreography since then, I have felt close to the work aesthetically and emotionally. On this occasion I would like to talk about the two categories of gifts she gave us: as an artist and as a leader.

Redefining DanceWho would have thought that a dance could consist of the audience lying on their backs and looking up at the ceiling to imagine seeing what Trisha’s voice is telling them? (That was Skymap, 1969.) Who would have thought that two people surprising each other with what direction they would fall toward could be a piece of choreography? (That was Falling Duets, 1968.) Who would have thought that the optical illusion created by people walking on walls could hold the attention for a good thirty minutes? (Walking on the Walls, 1971.) Not me. But when I saw her concert at the Whitney Museum in 1971, these three actions were thrilling — kinetically, intellectually, perceptually.

Now, years later, I can rub my chin and say, “Ah yes, I see the influences of Anna Halprin, Simone Forti, Yvonne Rainer, or Steve Paxton.” But at the time, this event gave me a pleasant shock that brought me up close to Trisha’s singular imagination. I wanted to dance that way — with an alert mind and a relaxed, pleasurable body.

She has said she felt sorry for spaces that weren’t center stage — the ceiling, walls, corners, and wing space. Not to mention trees, lakes, and firehouses. She caused a revolution by simply, sweetly, turning to spaces that other dance-makers don’t. But she also caused a revolution in the space of the human body. She rejected the pulled up stance of ballet and the inner torque of Martha Graham. She loved Merce Cunningham’s work but she had no wish for dancing bodies to be so upright. She was going for something else, something more yielding, more off-balance, a way for the energy to flow on unusual paths through the body. In her choreography the pleasure of surrender coexists with the willpower of adhering to a rigorous structure. (For a full bio of the choreographer, click here.)

Starting with Improvisation

Trisha’s earliest works were improvised. She had learned to deploy simple structures from Halprin when she studied with her in California in 1960. In Trillium (1961) she took a basic improvisation exercise to choose when to lie down, sit, or jump, and did it her own way. “I made my decision about lying down and jumping at the same time,” she said in a 1980 interview.By all accounts, Trillium was a wild solo that made people believe she could be suspended in the air.

Trisha often asked her dancers to improvise based on either a loose idea (e.g. “Line up” or “Read the walls”) or quite tight verbal instructions. She wanted the look of improvisation, the feel of not knowing what you were doing until you did it. That aesthetic reached its apex in Water Motor (1978). Babette Mangolte’s film of that exhilarating solo has become essential viewing for students of postmodern dance.

When she taught us a choreographic sequence, her movement was so elusive that I remember thinking, “She teaches it as a solid but she dances it like a liquid.” The key to attaining that liquid quality was to know in your own body how one impulse triggers another, to know exactly what and when to let go. While Trisha rejects the term “release technique,” the dancers have to be precise about utilizing release as well as strength.

Lines vs. Chaos, Rigor vs. Sensuality

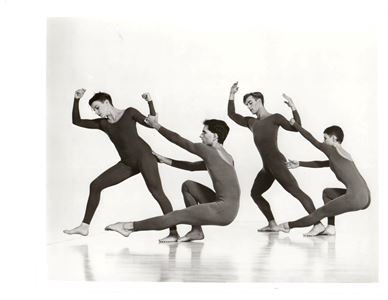

The lovely paradox is that she also insisted on containing this sense of discovery within a rigorous visual or mathematical order. In Line Up of the mid ’70s, lines of people would materialize and dissolve — like following one’s own thoughts.

She brought nature into the studio. She loved her home territory of the Pacific Northwest and, come summer, she often returned there to take her son backpacking. While teaching one phrase of “Solo Olos” (part of Line Up) she said, “Imagine you are seeing Puget Sound in the distance and are tracing the length of it with your fingers.”

But it wasn’t landscapes alone that captivated her; it was the human body in an environment, for example the inevitable sensuality of the body up against the absoluteness of lines. In Group Primary Accumulation (1973), four or five prone women move the right arm from the elbow down, then repeat that, then go on to the second move of raising the left arm from the shoulder, repeat both and so on, up to 30 moves. The pelvis lifts softly on move # 7—in a meditative way of course. The dance is incredibly sensual to do and to see, and yet the accumulation score keeps the mind strictly focused. (Click here to see a clip of a 2008 performance of it in Paris.) While we were on tour, Trisha once said, “When I am doing Primary, I’m thinking, ‘This is all there is.’ ”

And then there’s the delightful Spanish Dance (1973), wherein five women tread slowly across the stage, accumulating one at a time to form a crush of bodies that hits the proscenium wall on the last note of Bob Dylan singing Gordon Lightfoot’s “Early Morning Rain.” While nothing much happens, each woman is sandwiched by others, flesh on flesh, swaying pelvis on swaying pelvis. The audience can see where the line of women is heading but the physicality of it still elicits chuckles of delight.

Simplicity to Sublime Chaos

Over the years — Brown created about 100 works including operas — I felt I was seeing a progression from simplicity to complexity, from clear strategies to hidden strategies, from orderliness to a sublime chaos. Set and Reset (1983), with is free form look and lids-off sense of play, definitely qualifies as sublime chaos. With music by Laurie Anderson and set by Robert Rauschenberg, it’s a masterwork that bears repeated viewing. It offers a sense of possibility, a sense of the dancers being ready for anything. While jogging from upstage to downstage, Stephen Petronio suddenly gets pulled offstage by Trisha grabbing his neck. Another time, Trisha dives into the arms of another dancer who seems to be looking the other way. Set and Reset is so overflowing with possibility, with unpredictable interactions and close calls, that it took me three times of seeing it to realize that simple walking and running are also woven into the dance. She is teaching us to see things that are not obvious.

Her trajectory of simplicity to chaos is paralleled by the trajectory of earth to air. Just as she managed to catapult herself to be prone in the air for Trillium, and horizontal while walking on the walls of the Whitney, she set dancers above the ground — floating with help, one might call it — in Planes (1968), Floor of the Forest (1970) and Lateral Pass (1985). And then, in the opera L’Orfeo (1998), she created an extended passage for Diane Madden to be airborne, floating as the demigod, Musica, rigged by the ultimate professional riggers, Flying by Foy.

Dance and Visual Art

Part of Trisha’s vision has to do with giving dance the same seriousness accorded visual art. That means bestowing it with intellectual attention. It also means, in the balance of art and entertainment, tipping more toward art and less toward entertainment. When we gave lecture-demonstrations and the question came up, “Why don’t you dance to music?” she would counter with, “Do you walk around a piece of sculpture and ask why there is no music?” Now that we are engulfed in a wave of dance in museums, I feel it’s still Trisha’s early work, the silent pieces oriented around lines, that fit so nicely into the museum milieu.

After all, she is a visual artist too, and her drawings have been shown in galleries in the U.S. and abroad. It was natural to her to collaborate with some of the best artists of our time, including Robert Rauschenberg, Nancy Graves, Donald Judd, and Elizabeth Murray.

Going Back to the Beginning

Her vision also had to do with going back to the beginning, questioning the assumptions that have built up and figuring things out for yourself. In clearing the air of “modern dance” histrionics, of course she had comrades in Judson Dance Theater like Yvonne Rainer and Steve Paxton. Yvonne ran or screamed, Steve walked, and Trisha fell. While that’s a gross exaggeration of the ground-breaking experiments at Judson, it shows how committed they were to getting down to basics; how much they aimed for the “ordinary” (to use their teacher Robert Dunn’s term).

For Trisha that meant channeling the radical into an ordinary container. In the ’70s she wrote a statement on “pure movement” that included this: “I make radical changes in a mundane way.” (Click here to read her full statement on Pure Movement.)

When she started making works for the proscenium stage, she started at the beginning again, asking herself what was essential about the stage. She enlisted Rauschenberg’s help in questioning the conventions of the stage. In Glacial Decoy (1979), they both envisioned the dance extending beyond the proscenium, creating the illusion that the dancers did not stop at the wings. For Set and Reset (1983), he made the stage wings transparent, blurring the difference between performing and not performing.

Her Influence

Trisha Brown’s influence is larger than we can ever know. Young dancers see her work in a studio or in performance and learn how good it feels on their bodies. They may incorporate a version of her style, which tends to fold the body along different lines than in “modern dance.” There’s a respect for the plainness, the sensuality of simple movements framed by rigorous scores (structures). Even if they haven’t seen it first-hand, her way of moving is now in the air. It’s like a Trisha Brown mist that dancers all over the world are breathing in.

Do you remember the beginning of Set and Reset, when several dancers hoist one in the air so she can be horizontal and walk on the wall? I’ve seen this echoed many times in the work of others, most recently last month at Sadler’s Wells in London, during Partita 2, a collaboration between Anne Teresa de Keersmaeker and Boris Charmatz.

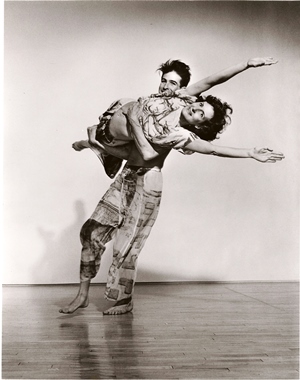

And then there are those who imitate Trisha very deliberately. Last year Beth Gill’s New Work for the Desert borrowed liberally from Brown’s 1987 Newark (Niweweorce). At the end of Newark there’s a double duet made of new and strange ways of leveraging each other’s bodies: holding or pulling by the neck and hooking an ankle — almost animal-like — though again, within strict lines. In this interview with Gia Kourlas, Gill says that she studied this section on video and incorporated it into her work.

Of course it’s fair to study an older artist’s work, but appropriating it is another story, maybe even a legal one. However I think the fact that Gill paid Brown tribute in this way speaks to how iconic Trisha’s work has become. It’s like Rauschenberg erasing a drawing by de Kooning, or Van Gogh copying whole scenes from Hiroshige.

Generosity

Trisha was always generous in her encouragement to dancers like Stephen Petronio and me, who were choreographing on our own. She once hosted a small gathering for possible funders to see my work, and she gave Stephen access to studio space in her building.

But most of all, she was generous to the dancers within her work. I spoke on the phone with Diane Madden, who has been a member of the Trisha Brown Dance Company since 1980, first as a dancer then rehearsal director and now co-associate artistic director. “She created a clear space that allows people to have lots of room,” Diane said. “You felt trusted by her, which allowed you to take more risks and give more. … She would give us very clear guidelines, whether working around the perimeter of the space, or keeping close proximity to the floor, working in slow motion, but wouldn’t over-define or over-direct.… She would challenge you to go beyond your comfort zone because she was always challenging herself. We all were challenged.”

In 1984 she asked Diane to become rehearsal director. “There would get to be a point,” Diane told me, “where the managerial role of taking care of the dancers’ needs had to be separate from the creating process. Things would happen that would turn her off or piss her off, and she didn’t want that to sully her creative relationship with the dancers.”

I always felt that Trisha had an awareness of herself as a woman leader, and Diane agrees. “It was important to her to lead well, to make sure she was making all the right choices,” she said. “She wanted to be a good role model for other choreographers and dancers.”

Choreographer Stephen Petronio, who danced in the company from 1979 to 1986, has been outspoken about her influence. “The air of democracy in the room — I emulate that,” he told me. “I learned to be inclusive and democratic from her. She always made me feel part of the team, not her slave, and that made me want to give everything I have.”

Endings Are Beginnings

I’ve noticed that in some of Trisha’s most beautiful works, for instance Opal Loop (1980), Lateral Pass, and Newark, the last segment ushers in an entirely different sequence from what came before. These non-conclusive endings break so clearly from the rest of the piece that they could be the beginnings of something else.

In that spirit, I am going to end with a beginning. The Trisha Brown Dance Company (TBDC) has just initiated a new series called In Plain Site. For medical reasons Trisha withdrew from making new work in 2011, and the company took on a three-year legacy tour of the proscenium works under the direction of Diane and the other associate artistic director, Carolyn Lucas. Now, the company will perform in non-proscenium spaces; the rep will include not only the early works that fit so well in museums, galleries, and outdoor areas, but also snippets from the proscenium works. It will be a bit like Merce Cunningham’s “events” — each tailored to a different space.

The education projects of TBDC continue apace in colleges and dance centers in the U.S. and in Europe, where Trisha is especially lionized. As an alumna who occasionally leads these classes, I can say that students everywhere continue to find the keys that open doors to personal discovery within the vast and challenging oeuvre of Trisha Brown.

Wendy Perron danced with Trisha Brown from 1975 to 1978. She has also choreographed more than 40 works for her own company. Her book of selected writings (Through the Eyes of a Dancer, Wesleyan University Press, 2013) includes several articles on Brown’s work. She has taught aspects of dance at Bennington, Princeton and NYU Tisch School of the Arts and has been a guest teacher or lecturer across the country. She has written for The New York Times, The Village Voice, Dance Europe and Dance Magazine, where she was editor in chief from 2004 to 2013. The New York Foundation of the Arts inducted her into its Hall of Fame in 2011. She currently posts commentary and previews on her own site at wendyperron.com. And, occasionally, she still dances with her sister in Trisha-love, choreographer Vicky Shick.

Resources

Website:http://www.trishabrowncompany.org/

DVD: ArtPix DVD: Trisha Brown: Early Works 1966-1979 (http://www.artpix.org/02TB.htm)

Books:

Trisha Brown: Dance and Art in Dialogue 1961-2001, Hendel Teicher, ed., published by Addison Gallery of American Art and distributed by MIT Press.

“Trisha Brown: Gravity and Levity” in Terpsichore in Sneakers, by Sally Banes, Wesleyan University, 1987.

____

We accept submissions on topics relevant to the field: advocacy, artistic issues, arts policy, community building, development, employment, engagement, touring, and other topics that deal with the business of dance. We cannot publish criticism, single-company season announcements, and single-company or single artist profiles. Additionally, we welcome feedback on articles. If you have a topic that you would like to see addressed or feedback, please contact communications@danceusa.org.

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed in guest posts do not necessarily represent the viewpoints of Dance/USA.