Choreographing Disability Justice: Dancemakers Antoine Hunter and Laurel Lawson

By Jerron Herman

Editor’s note: This article is one of 11 in a series examining the creative work of 31 dance artists funded by Dance/USA Fellowship to Artists, generously supported by the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation. These artists’ practices are embedded in social change as they work in multiple dance forms in communities across the country. Image descriptions appear at the end of the article.

Laurel Lawson, a white woman, balances on the footplate of Alice Sheppard’s wheelchair, with arms spread wide, wheels spinning. Alice, a light-skinned Black woman, opens her arms wide to receive her in an embrace. They make eye contact and smile. A starry sky fills the background, and moonlight glints off their rims. Photo: BRITT / Jay Newman

It’s clear to those within, but possibly not to those outside, that the disability and Deaf communities are not monolithic: Engaging with one is not engaging with everyone. Amid a plethora of cultural and vocabulary distinctions within the Disability Arts Movement, a growing field of artists who produce exciting and probing work, two denizens are Atlanta-based Laurel Lawson and San Francisco Bay Area-based Antoine Hunter. Both dancer/choreographers debuted works for Dancing Wheels Company’s 2019 season, which coincided with the Dance/USA Annual Conference in Cleveland, where the 40-year-old company is based. The two artists animated the Dancing Wheels Company in vastly different ways, like Hunter’s invocation of sign language to mirror a design element or Lawson enhancing the synchronicity of wheelchair-using and standing dancers’ movement. However, amid noticeable distinctions, a foundational core exists, informed by Disability Justice, the political framework for interrogatory access and care work, interdependence and equity, on which most disabled and Deaf artists seem to draw. These artists place their work within a political ideation.

Paraphrasing disability scholar Simi Linton, dancing while disabled is a political act. This reality means that disabled and Deaf artists must ensure spaces are welcoming. That can mean using physical and culturally accessible practices that range from a ramp to a sliding-scale pay option. They must develop specific modes of engagement with audiences that include ASL interpreters and audio describers, often at the onset of their creative process, and share informed ingenuity in storytelling. Indeed, as I spoke with Lawson and Hunter about their processes, their parallel actions as activists uncovered deeper reasons to make dances.

When Hunter, who is also Two-Spirit, Cherokee, and Blackfoot, founded the Bay Area International Deaf Dance Festival in 2013, it was in part to expand connections among other Deaf artists. Fiercely committed to the Deaf community with his own company, Urban Jazz Dance Company, he sought to create an international forum where Deaf artists could come together and insularly ask what they needed. Though there are scheduled classes and performances, his festival is organized like a large cipher. Signing is understood as regionally specific — with different languages and dialects in different countries and regions; similarly, in artistic circles its use is contextual. Using sign as poetry differs from its use to interpret a song. In dance, signing use broadens to incorporate the whole body, sometimes divorcing typical practices like synchronous facial expression. Signing used this way creates new movement vocabulary both for the Deaf and general dance communities.

SIGN LANGUAGE DEEPENS MEANING

Purple Fire Crow, also known as Antoine Hunter, is bare chested, his hands gesturing toward his face. He is an award-winning African, Indigenous, Deaf, Disabled, Two Spirit producer, choreographer, film/theater actor, dancer, speaker, mentor, and Deaf advocate. He is founder of Bay Area International Deaf Dance Festival, Urban Jazz Dance Company, and #DeafWoke talk show. Photo: RJ Muna

Hunter was primarily interested in a Deaf festival because he felt that Deaf people must be centered and acknowledged when using sign language because it extends beyond a communication tool. Sign language relays meaning in an interwoven fashion, drawing on emotion, speed, and compound gestures (versus finger spelling), which go further than a direct English translation. For Hunter, signing is responsive: “I have support from the Deaf community and the hearing community to hear what they see and feel because I want it to be the truth.” Because sign language has region-specific phrasing, it provides opportunities to deliver complex messages to audiences and artists, elaborating on issues like literacy or health care within the Deaf community. These messages land palpably when audiences interpret how artists use subtext — shade — or common daily gestures. This galvanizes them by virtue of a shared experience. An international Deaf festival also builds a link between global communities to end stigmatization. Brazilian artists, for example, can introduce Bay Area artists to new sign and dance vocabulary and vice versa, expanding their practices just as attending an intensive does for another dance form, but deeper somehow.

At the core of Hunter’s philosophy is communication: “The truth of my work is in finding that language to work all together. What’s the language of having more time? … When we have more time, we start to know how to move our bodies differently.” He notes that when you learn new forms, you connect with all the elements: your body, prevailing histories, nature, your neighbors. Deaf arts continue to evolve as different cultural practices become more widely used and Hunter is experimenting. He wants to employ haptics, vibration technology, in seats at future festivals so that music can be felt, even if it’s not heard, as the artist desires. He discovered ways to partner with the Deaf-blind community, which uses Pro-Tactile (PT) sign language to expand usual sign language by interpreting gestures on several levels. The Deaf-blind speaker utilizes another body as a canvas to relay something, while a number of interpreters surround them, finger tapping affirmation or environmental cues on the speakers’ bodies; one person interprets everything in a spoken language for an audience. Because PT is created and interpreted in a group, it naturally implies deep community connection as speakers must sense and notice even the smallest gesture as significant. Therefore, Hunter values more time to process, relay, and create. Hunter’s practice is deepened by how language fits in different contexts. Ultimately, he wants people to relate to each other with their humanity.

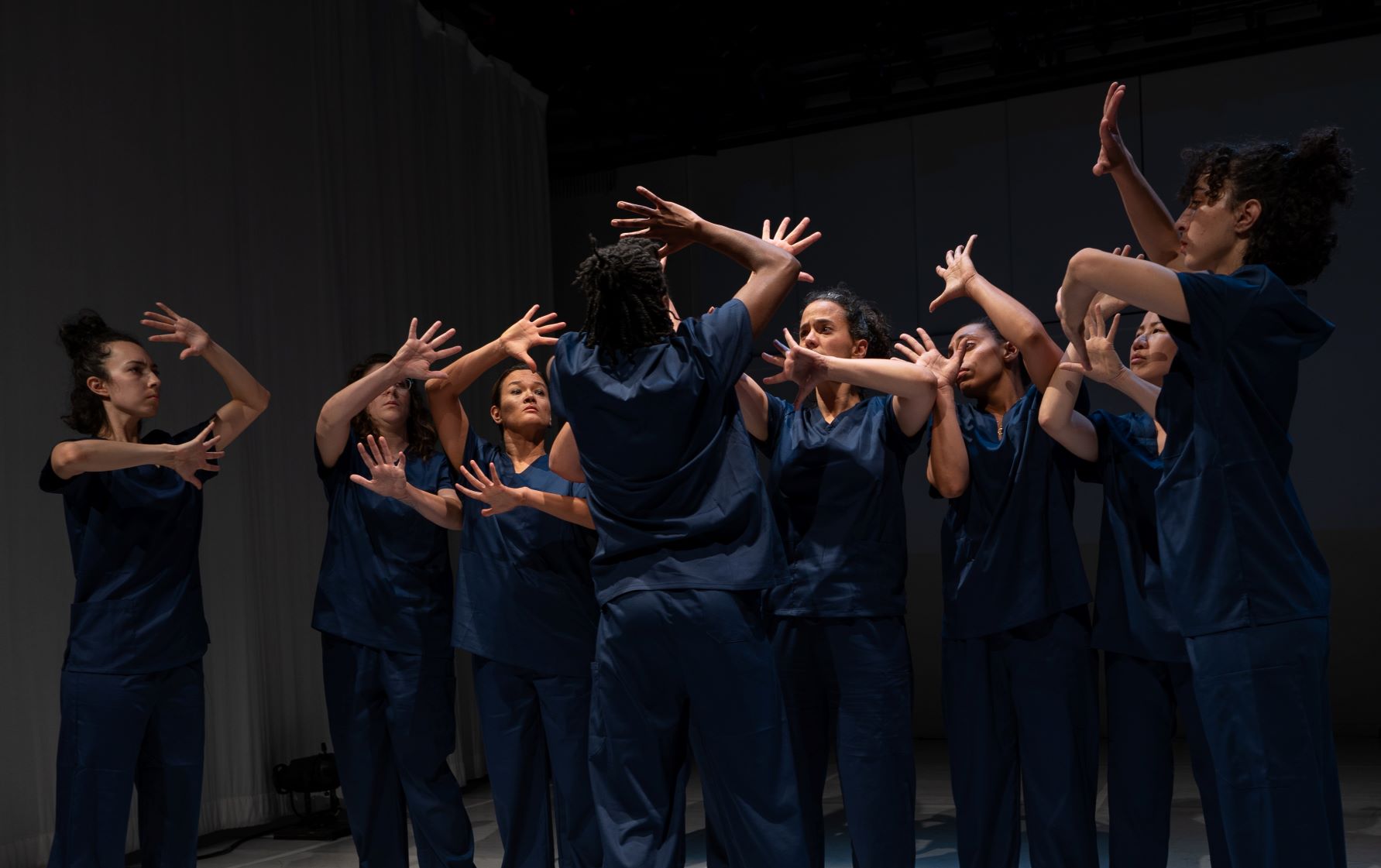

Hunter’s Deaf’s IMPRISONED explores what it means to be in a “prison within a prison” as a Deaf person moving through the criminal justice system. A group of performers in dark blue garments stretch their hands in front of their faces. The 2018 Urban Jazz Dance Company work navigates the tension between what Hunter called Deaf utopia and Deaf diaspora. Photo: Robbie Sweeny

A still complex subject for the dance artist is how the larger Black dance community often excludes him, he said, seeing him as just, or primarily, a Deaf man, and not noticing that race, too, is uniquely tied to his work. In his company’s piece, Deaf’s IMPRISONED, Hunter explored the multiple schemas of oppression while incarcerated — Black, female, male, and Deaf — giving concrete examples of the intersections of race and disability. He hopes to build a stronger link with the Black dance community through the kind of challenging works that, he says, people don’t really want to talk about.

As a DFA fellow he’s been able to imagine his work beyond industry and nonprofit dance limitations for the first time, giving him a chance to “breathe above the water; to dream.” It legitimizes his years of scholarship and exploration with artistic forms for the Deaf community. His commitment to Deaf artists, especially women and people of color, is reflected in the staff he hires and the productions he mounts. For example, when he used British Sign Language in a revival of Deaf’s IMPRISONED in the U.K., Hunter led British communities to question legacies of colonialism, literacy rates among Deaf people, and the prison system. That shifts how disability can narrate complex ideas in society through art. As multiple international Deaf dance festivals sprout — often with Hunter’s help — the connections sown from earlier experiments drastically deepen the artistic experience for all.

While using technology in dance works often enhances production, I doubt our current paradigm would call it justice, but dancer/choreographer Laurel Lawson would. An artist-engineer, Lawson’s curious mind is informed by years of political activism and software engineering. She united her powers and skills: Lawson first trained and worked with disability policy groups in Washington, D.C. Later she became a member of Full Radius Dance (FRD), the Atlanta-based physically integrated dance company. Finally, her interest in creating new things and solving problems led her to co-found the tech company CyCore Systems in 2004, the year she began dancing professionally. CyCore is an architecture and design consultancy that focuses on solving new problems in and with technology, particularly in communications and user interfaces. Lawson’s expertise in ethical technology, access, bright patterns, and social justice makes her a sought-after speaker in the technical world.

LINKING ARTISTRY WITH ACTIVISM

Lawson balances on one wheel, tilting away from the camera. She throws her arms overhead and looks at the viewer. Lush greenery is in the background. Lawson found that dance combined her lifelong loves of art and athleticism. Photo: Hayim Heron/Jacob’s Pillow

The strong link between Lawson’s artistry and activism is evident because she has spent considerable time developing skills across all her media: politics, engineering, and dance. She thrives in all three fields and can’t imagine not working in each: “I do not know how to be in the world without acting against injustice.” Dance helps her combat injustice as it creates a dynamic means to address it, she says. Lawson is passionate about training and developing new disabled talent. While some disabled dancers, she explained, may use multiple devices like wheelchairs, crutches, or floorwork to live and work, when teaching new dancers this work, Lawson encourages them to focus on one embodiment for at least their first year of training. She cites embodiment theory, the concept that bodily experience and processes help us understand emotional experiences. Lawson says: “People who use different modalities can have multiple bodies, which require separate training and technique.” Yes, many bodies. The theory claims that the apparatus is part of the body and transforms not only the person’s physiology, but their emotional perceptions of it, and of the world around them. The wheelchair is vastly different from crutches or the floor and each ought to be examined deeply by dancers in training, she noted. Lawson plans to publish a manual, particularly on wheelchair technique, illustrating specific disabled movement vocabulary that will expand disabled representation.

As a choreographer, she’s working to “tell a good story” and believes everyone should have an equitable experience of that story. Through Audimance, a performance app under development, users can interpret an onstage work through multiple forms like audio and text description, but also sonography: the sounds of how feet or wheels communicate the movement’s tempo and luster. Poetry, or elevated textual descriptions, also communicate the motion. All these elements coalesce into a 360-degree experience. One implication, in line with disability culture, is how the app normalizes the presence of multiple intelligences. This technology feature enhances the growing offerings of Kinetic Light, the disabled-led company started by dancer/choreographer Alice Sheppard, designer Michael Maag, and Lawson. Alongside their rigorous dance-making and film work, their innovative access work, like Audimance, sets them apart in the arts field. As she finishes her fellowship period, Lawson is resolved to bring more disabled people to dance.

Both Hunter and Lawson are just getting started. Though they’ve already paved dynamic pathways for other disabled and Deaf artists to follow, there’s more to be done to deepen appreciation of disabled and Deaf offerings among audiences and presenting institutions. The future of Deaf and disabled dance is in Disability Justice concepts like interdependence and access intimacy, which help these artists genuinely participate in the field. As their works continue to interrogate “dance” with different storytelling devices, different bodies, and different approaches, Hunter and Lawson are expanding dance for all.

Jerron Herman is a dancer and cultural critic. He recently developed a panel series of disabled artists called Access 2.0: Mapping Accessibility for the Shelley & Donald Rubin Foundation. His latest works include Breaking and Entering for Danspace Project, Many Ways to Raise a Fist for The Whitney Museum, and Relative for Performance Space New York. He has served on the Board of Trustees at Dance/USA since 2017 and was nominated for a Dance Fellowship from United States Artists. Jerron studied at NYU’s Tisch School of the Arts and graduated from The King’s College. The New York Times has called him “… the inexhaustible Mr. Herman.” For more, visit jerronherman.com.

Readers may read and print a PDF version of this article here. Readers may visit and share this article on Medium here. Please visit the artists’ websites: Antoine Hunter and Laurel Lawson. Find more information on the DFA Article Series here and more information on Dance/USA Fellowships to Artists here.

____

We accept submissions on topics relevant to the field: advocacy, artistic issues, arts policy, community building, development, employment, engagement, touring, and other topics that deal with the business of dance. We cannot publish criticism, single-company season announcements, and single-company or single artist profiles. Additionally, we welcome feedback on articles. If you have a topic that you would like to see addressed or feedback, please contact communications@danceusa.org.

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed in guest posts do not necessarily represent the viewpoints of Dance/USA.