Tips from Patsy Gay, Associate Archivist, Jacob’s Pillow, and Kamala Cesar, Executive/Artistic Director, Lotus Music and Dance

By Hallie Chametzky

Editor’s note: The COVID-19 pandemic and the requirements of social distancing have led dance artists and companies to embrace the digital: offering remote classes or rehearsals, streaming archival or new performances. In Part 2, Patsy Gay, associate archivist at Jacob’s Pillow, and Kamala Cesar, executive/artistic director of Lotus Music and Dance, discuss archiving dance collections. You may read Part 1 at this link. More practical tips and guidelines for archiving during the pandemic can be found at Dance/USA’s Archiving During the Coronavirus webpage.

For more insight into the relationship between dance and archiving, especially during the COVID-19 global pandemic, we spoke with Patsy Gay, associate archivist at Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival, the United States’ longest running dance festival with extensive archives going back to the festival’s founding in the 1930s all the way through today. Kamala Cesar, executive/artistic director of Lotus Music & Dance, describes the company as “a performance space, sanctuary, and center of education for traditional and indigenous performing arts forms,” and has worked with Dance/USA and the New York Public Library on the preservation of the collections.

Patsy Gay

Gay by Grace Landefeld, courtesy of Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival

Dance/USA: What are your top Dos and Don’ts for artists working on their physical and/or digital archives from home?

Patsy Gay: Any progress is good progress. It can seem like such a daunting thing, especially when you’re having to dive back into your entire history or looking at decades of materials, but any work is good work. It all moves forward in small steps.

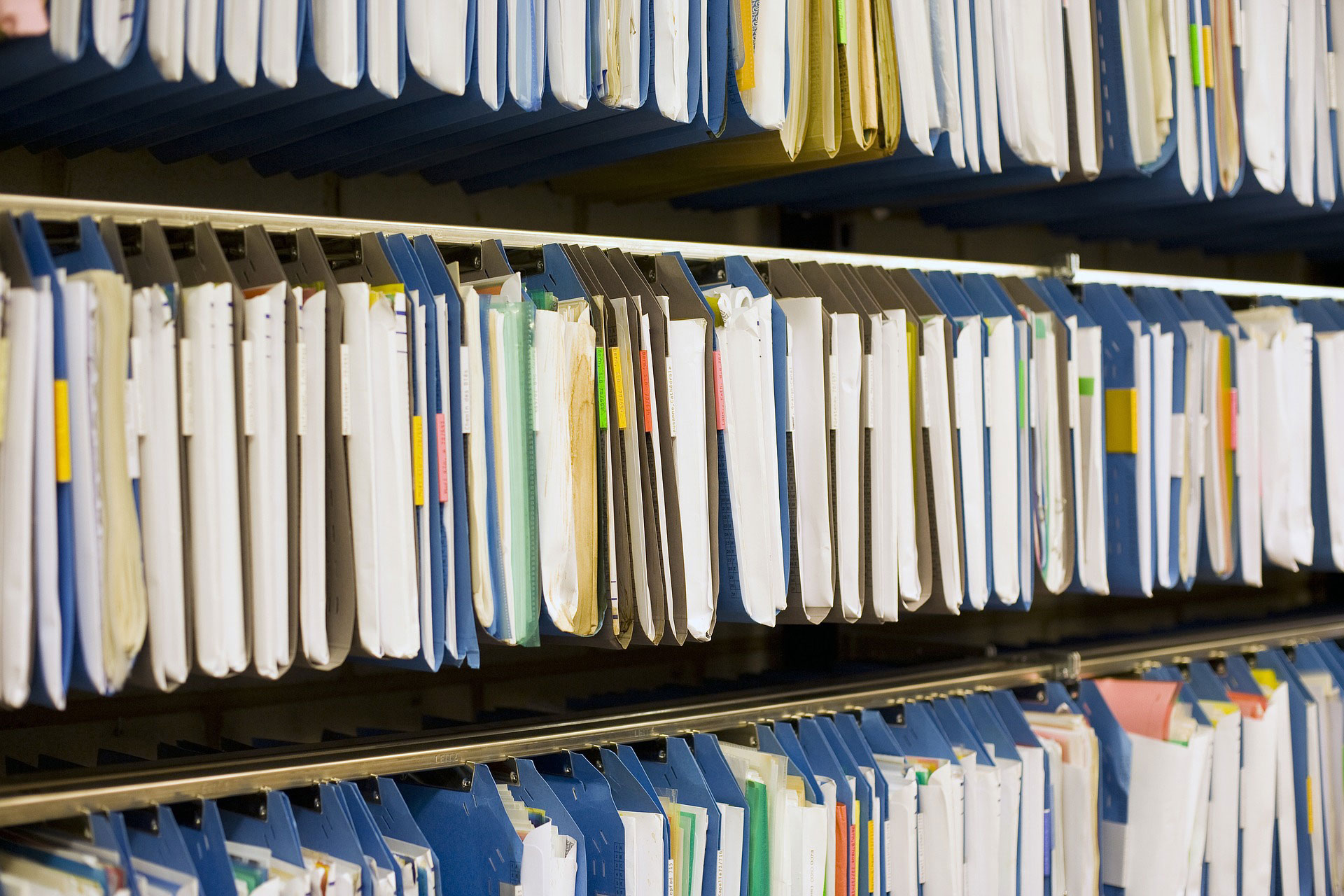

As long as you’re not doing anything damaging to the materials — please don’t put tape onto photographs or papers, burn things onto DVDs then throw away the originals, write in permanent pen on your paper items — any work towards organization is important work. It can feel like, “What I’m doing doesn’t matter” or “It’s too big of a project.” Just put them in folders! That’s wonderful. That’s huge progress, which will get you toward being able to actually use and engage with these materials.

It’s such a special time when an archive is still with the actual creating artist. They have so much information, perspective, and knowledge. Once it gets to an institution, it will be well cared for, but [the institution’s archivists] can’t contextualize, they can’t add history. Even more important than putting it in folders right now is seeing what’s there and what an artist could add. What story is missing? What information is not there? Maybe it’s just jotting down a note in pencil on the back of that photograph explaining why it’s important or interesting. Maybe it’s sitting down in front of your iPhone and reminiscing, giving your own little oral history about what the vision behind the work was. Maybe it’s creating some new piece of artwork that shows why a piece is important, all of which are things only the artist knows. Having this time is so valuable. I’m not trying to shame artists who feel like they can’t do this, they don’t have the time, or it’s too hard, but if this is seeming like a gift and a possibility, take that time to add the context and history that only the artist can.

D/USA: What do you see as the importance of archives in a time of crisis like this?

.jpg)

Pearl Primus and John Lindquist by John Van Lund, 1950, courtesy of Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival Archives, ©Harvard Theatre Collection

P.G.: Since we can’t have live performance, we’re seeing the importance and the power of documentation — photographs, video, films. They can be meaningful sources of engagement. Even more than just putting it up on YouTube, these can be sources of new inspiration, new creation, new conversation.

Whether it’s the Alvin Ailey dancers recreating works at home and stitching that video together, or the Martha Graham company putting works up online and having active, new conversations around them, documented archival work can be really generative and engaging. It’s been really eye-opening to a lot of institutions and to our field more broadly. It’s really exciting, actually. Archives can often be the last thing that’s thought about, both in institutional man-power and funding. It’s been really interesting to be in a crisis where the archives suddenly might be the most important thing an institution has. I hope it will change how documentation and archiving is viewed in the future, which would be an amazing silver lining out of this terrible time.

D/USA: In your current role, how are the archives being utilized? Has the approach changed in the past few months?

P.G.: We [Jacob’s Pillow] are blessed to have an archival presence unlike many institutions. We are very publicly visible and we’ve been very engagement focused. Also, we have a deep history of audience engagement — our audience-engagement program is over two decades old. We are poised in a really unique way to be able to share this historical content, but also have the skills around contextualizing that content. We are able, like with the Judith Jamison talk that we showed, to screen these archival materials, and also have that be a site of generating new conversation and ideas, which is really exciting.

D/USA: For dance companies and organizations who don’t have as robust a background in that, it can be a good model.

Blake’s Barn houses the extensive Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival archives and contains exhibition space for photos and materials from the collection, by Grace Landefeld, courtesy of Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival Archives

P.G.: The archive isn’t the end, it’s the starting point. You’re putting that up, then you’re using that to drive conversation, drive new engagement, to drive generative inspiration for other artists or your own work.

D/USA: How might archives and archivists be able to help artists remotely during this time?

P.G.: Our ability to share artists’ work, have the platform to share them, and connect with the artists so that they can become part of the conversation, is something we are uniquely poised to do.

Also, being able to provide material to artists who might not have it. It’s their own work, it’s their own documentation, but maybe they weren’t at a place two, five, ten, fifteen years ago to be able to steward that documentation, but we are. Artists are coming to us who want that content — that is their own copyright, their own artistic product — and we’re able to provide that for them.

Dance/USA and other activist/artist/archival organizations have been providing tools and skills to artists; that has been really valuable right now. Especially because we’re seeing that in this crisis, like so often happens, the most vulnerable parts of our population are the first to go. It’s our part-time workers, contingent labor, Black, Indigenous, people of color, lower economic brackets. It’s artists. They are some of the first to suffer, they have the fewest safety nets, the least social structures supporting them. So, if artists are telling their own story, documenting themselves — also documenting the story of right now, which is something that needs to happen — repositories, hopefully, will catch up.

We’ve been working hard in the archives field to collect voices that aren’t necessarily the dominant voice, but that’s still a process. If artists, if Black, Indigenous, people of color, aren’t able to create and save their materials, there will be nothing left in five or ten years when an institution decides that that is an important voice and needs to be collected. We need as much information, resources, and guidelines that archivists can share with artists right now about how to create and save their materials so that the story exists and can become part of the dominant narrative. If the artist doesn’t do that in the first place, then that story doesn’t exist to be preserved and told.

- Jacob’s Pillow’s completed its first ever Virtual Festival utilizing archival recordings of beloved performances from the past 10 years shared every week, as well as talks, classes, and behind-the-scenes content. You may search the Pillow’s archival collections here.

Kamala Cesar

Cesar, courtesy Cesar

D/USA: What’s the biggest lesson you and your organization have learned through the process of archiving your materials?

K.C.: Especially now that we’re trying to find videos that might be good to put online during this lockdown period, we’re thinking about creating things that look good on a computer screen. The straight camera shot on a stage is okay for documenting that the event happened, but better camera work is going to be something that we will definitely consider. We’re thinking: How can it be viewed by a larger public? How should it be framed? How will it be used down the road? We’re trying to do the original shooting in higher quality or in a way that makes sense for viewing later on.

D/USA: What benefits have you found to having your materials archived?

K.C.: Being reminded of what we do have: taking inventory, taking stock, and then figuring out ways to make it useful to the artists who are in the videos. A lot of the artists that we’ve worked with are still teaching, or have their own companies, and I’m sure that those materials will be useful to them and their students. Being able to get that documentation to those artists and their students is a very big benefit for all of those dance forms. We’re trying to figure out the best way to do that.

Once the [New York Public] Library takes the collection, it’ll be even more accessible. The benefit of having the library take, especially, the tape formats is that we are not able to really store them properly, being a small organization and just having [limited] office space or storage space. [The library] will take them, store them properly, and digitize those tapes, which is something we never would have been able to afford to do. We were struggling with how to do it. While we can do some ourselves, we’re not set up to digitize the whole collection because it’s just too much. It’s been a really wonderful relationship because there’s a lot of other stuff that they [NYPL] do, and it’s all done so well, so I’m really glad that the collection is going there.

D/USA: What advice would you give to artists beginning to think about conceptualizing, organizing, and publicly sharing their archival materials?

K.C.: I would strongly urge them to become members of organizations like Dance/USA and Dance/NYC so that they know what resources are out there and available to them. I remember I once found some online video resource, and I was trying to contact the person who was in charge, and I think somehow that’s how I found Imogen [Smith, Dance/USA’s Director of Archiving and Preservation].

Then, I started going to the Dance/NYC symposiums, and one of their workshops was specifically on archiving your work and how to deal with all of the videos you have all over the place. We had our own space, we had a whole floor in a building, and we had a special room just for the videotapes. But when we lost that space, we had to move into just an office space, so then we had to get storage space. That’s when it began becoming a concern, because not every storage space is climate controlled, and we certainly couldn’t afford to have such a space. We were storing these tapes in just a regular storage space and that didn’t seem like such a good idea. Other people were advising us that we needed to do something about getting them digitized because the tape formats didn’t have a very long lifespan. We applied for grant money to start doing the digitization ourselves, and that took forever to get. That takes us up to the present time when Imogen met with us and put us in touch with the NYPL.

.jpg)

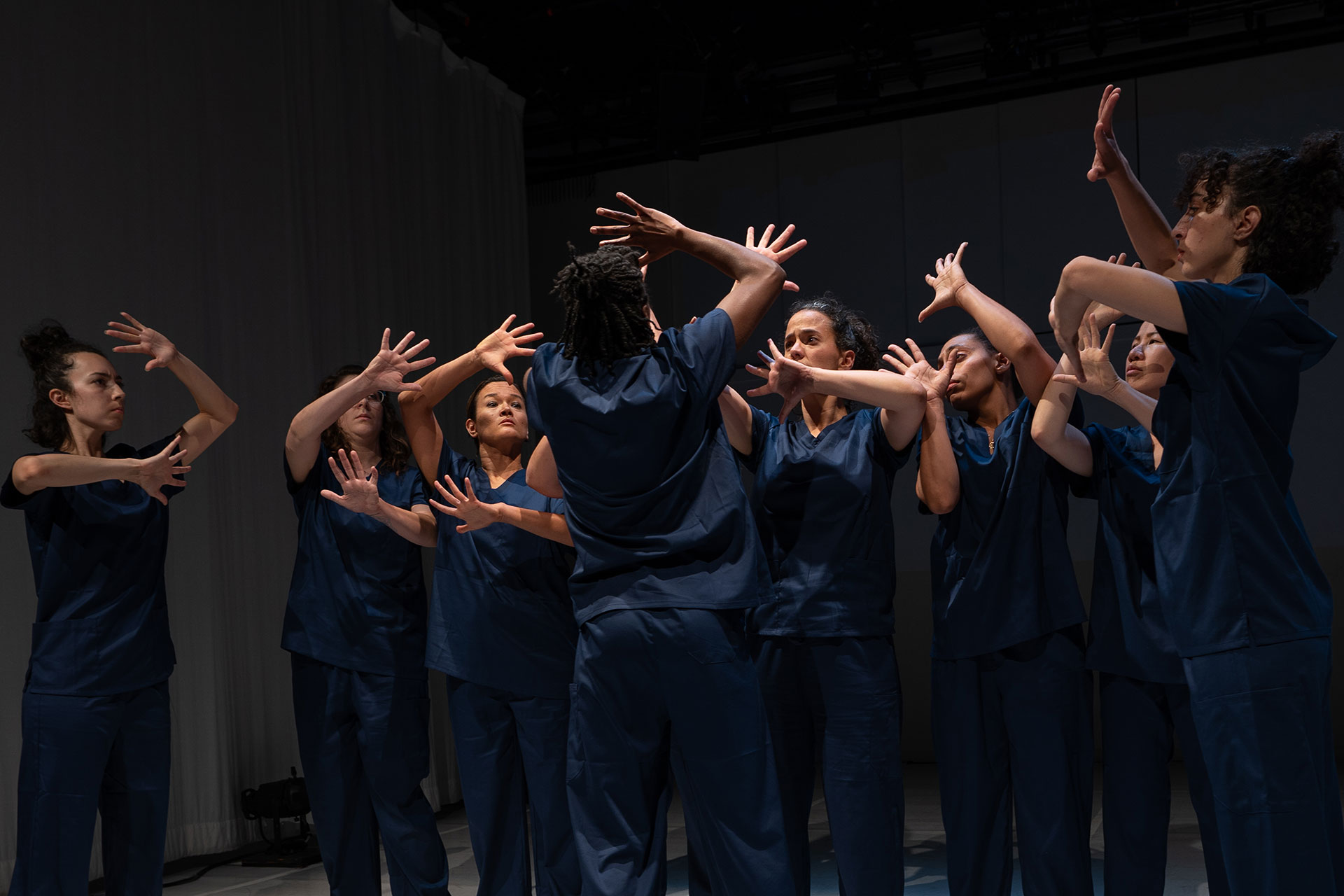

Lotus Music and Dance in “Asian Dialogue,” 2001, courtesy Cesar Chametzky by Zephyr Sheedy

It’s [working with organizations and libraries] definitely the way to go. There are resources out there that groups should be looking at from the beginning. Especially for dance, it’s such an important thing to have documentation of your work, because it’s such a visual form.

People don’t know where to start or what to do. Once Imogen got us going in the right direction, we thought, “Great! This is what we should be doing, and this is how we should do it going forward.” It’s really helpful to have access to resources, talk to other dance groups, and to go to symposiums. It’s really important to keep people connected.

D/USA: What do you think the role of a dance archive can be in a time of crisis like this? Has your relationship to your archive changed at all in the COVID-19 era?

K.C.: One of the problems that I’ve been experiencing with trying to teach remotely is the delay. There’s a slight delay in the sound and the image, so if you’re teaching a class, it’s almost ridiculous to try to really see what everyone is doing. While it depends on the dance form you’re teaching — Indian dance has to be extremely precise in the rhythmic parts of the dance, so it’s very disconcerting to teach class over Zoom — having video samples to share with students is going to be an important part of being able to teach effectively. Having the archive, I can find samples of what I’m teaching now if we’ve had a performance of it, or a previous workshop that got videotaped, and we have the section of that dance we need to share with students. For teaching, the archive is a great tool.

- Thanks to access to their archival materials, Lotus Music & Dance was able to convert the annual DRUMS ALONG THE HUDSON®: A Native American Festival and Multicultural Celebration to a virtual platform. The virtual performance features a retrospective of the past 18 years. For more information and to view some archival videos, click here.

Consult With a Dance/USA Archivist!

Have questions about archiving? Want to discuss your archiving goals? Book a phone consultation with Dance/USA archivists. An hour-long consultation is free for Dance/USA members and $40 for non-members. Find more information and how to schedule here.

Hallie Chametzky is the archiving specialist at Dance/USA. As a dancer and choreographer herself, her commitment to the preservation of dance history and legacy inform her practice, and are rooted in a deep respect for and love of the field. Hallie was a junior fellow in the Music Division of the Library of Congress where she processed, rehoused, and documented the thousands of items in the Sophie Maslow Papers, as well as other collections of the Martha Graham Legacy Project. She also served as an archives/audience engagement intern at Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival where she gained expertise in access-focused collections. Hallie is a graduate of Virginia Commonwealth University with a BFA in dance and choreography. She is also a freelance writer and poet.

____

We accept submissions on topics relevant to the field: advocacy, artistic issues, arts policy, community building, development, employment, engagement, touring, and other topics that deal with the business of dance. We cannot publish criticism, single-company season announcements, and single-company or single artist profiles. Additionally, we welcome feedback on articles. If you have a topic that you would like to see addressed or feedback, please contact communications@danceusa.org.

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed in guest posts do not necessarily represent the viewpoints of Dance/USA.