By Sarah Nguyễn

Sarah Nguyễn was a 2020/21 Dance/USA Archiving & Preservation Fellow. Phase 1 of their Fellowship ran from June-September 2020, and was hosted remotely by AXIS Dance Company. For Phase 2 in the summer of 2021, Sarah continued to work with AXIS, remotely and on site. Read more about the Fellowship program here. This is the second part of Sarah’s blog; find the first part here.

February 3, 2022: How to remember 16 years of dance through oral histories

I began the 2020 Summer Archiving Fellowship with AXIS Dance Company just barely six months after the WHO announced that we were (are still) in a global pandemic, so the original plan to convert the dusty basement storage into archives had to be adjusted. As mentioned in my Fall 2020 blog post, I was fortunate enough to spend time with AXIS Dance Company’s former Artistic Directors, Judith Smith (Emerita) and Marc Brew. At the time of the interviews, Brew was the active Artistic Director and still creating works and programming during mandated stay-at-home orders. Through all of this, Judy, Marc, and I collaborated to record AXIS Dance Company’s multi-perspective story.

A sepia tone photo of Judith Smith, AXIS Founder and Artistic Director Emerita, sitting in her wheelchair with her right arm reaching straight out to the right, head looking right, with dancer Janet Collard in back of Smith holding Smith’s arm out. Photo by Andrea Basile from KQED.

This blog will be reflective and instructional on my approach to the documentation of sixteen years of AXIS’ history through oral history preservation practices, inspired by the oral history practices I adopted from the New York Public Library Library for the Performing Arts Dance Oral History Project (s/o to Oral History Producer Cassie Mey!), Columbia Center for Oral History Research resources, and my own experience as a member of the Mark Morris Dance Group Archives Project team, directed by Stephanie Neel, under Cori Olinghouse’s mentorship.

A black & white photo of Marc Brew, AXIS Artistic Director and Choreographer, sitting in his wheelchair with arms caressing around his head and neck. His eyes are closed with a slight grin with the touch of his hands on his body. Photo by Nathan Lainé from @marc_brew Twitter.

While audio/visual recordings and storytelling are major components of the oral history practice, I will also emphasize the organizational, healing rituals, and empathetic practices we took on to create a physically and emotionally sustainable memory-making process for the artistic directors. Given the many hats that artists and arts administrators must wear, these should not be taken as prescriptive, standard practices but as a reflection on what worked for us given the context of the pandemic, and what might work for others seeking to record and preserve the long histories of their artistic works, through oral histories.

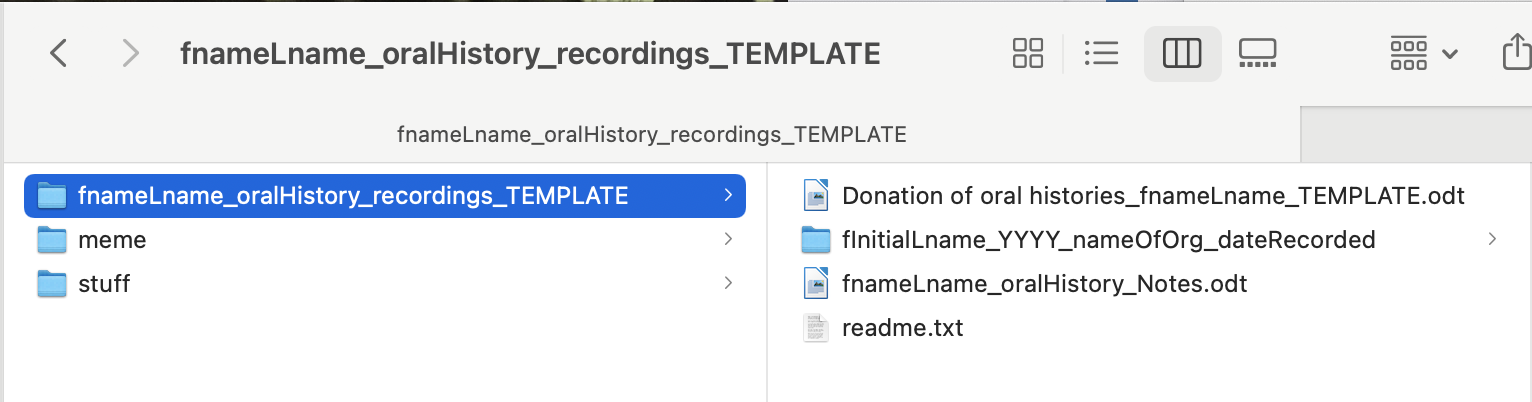

Here is a template folder that includes documents and folder hierarchies I created and compiled to organize all files related to the oral history interview(s). Throughout this post, I will reference the resources in the folder. Please do not hesitate to copy, adapt, and share the contents in this folder.

Organizing files produced from the oral histories

After ideating and manifesting inspiration around any project, one of the most difficult parts is to begin approaching a project with organized intention. Therefore, I advocate for any person to create and/or adopt a solid organizational system before embarking on recording interviews. My favorite resources on the importance and how-to of organization systems come from the Preserve This Podcast podcast (episode 2) and zine (page 7). Each person has their own best practices, so while these are suggested approaches, find the system that works best for you as a creator, and for the future viewers and listeners who you want to find the oral histories. Now, let’s dive into the organization system I set up for my interviews with Judy and Marc.

Each artist or administrator who will be interviewed for their oral history will have their own folder. See Screenshot A. This first-level folder will hold all research, recording, and administrative assets related to the oral history sessions of that one person.

Screenshot A: A screenshot of the folder hierarchy downloaded onto my personal desktop. I would keep the template folder as-is, copy the entire folder hierarchy, and change the folder name to the full name of the narrator, then delete “TEMPLATE” from the folder name.

First, I created a personal notes document, fnameLname_oralHistory_Notes, where I, the interviewer, outlined a to-do list for each narrator I’d interview—the narrator is the person who will be recorded telling their story. This helped me keep track of each task needed before, during, and after the oral history recordings. Here’s a review of the to-do list items and some notes on what each task entails:

- Research histories about [narrator]: It is important for the interviewer to come into each oral history session with knowledge about the narrator, events happening around the narrator’s life, and generally what was happening in the world.

- Draft oral history outline for YYYY to YYYY: Establish the timeline which the oral history will cover. With Judith, we decided to cover 2005 (picking up from the last year which her first oral history recording already covered) to 2017 (the year she passed the Artistic Director reins to Marc Brew). For Marc, we covered a broad overview of his life leading up to his time with AXIS, then the years of 2017 through present day (2020).

- Get Donation Agreement form signed (Donation of oral histories_fnameLname_TEMPLATE): The narrator(s) and interviewer needs to sign a donation agreement form before recording the interviews, if the artifacts from the oral history session will be stored and preserved with an institution. In this case, these recordings and transcripts will be donated to UC Berkeley Bancroft Library’s archives.

- [Mentor] to review oral history questions draft: During this fellowship, I received mentorship from Theresa Salazar, the Curator of UC Berkeley Library’s Bancroft Collection of Western Americana. She reviewed the lede and topic/question guide to ensure the activist, performance, and artist perspectives would be discussed.

- Finalize draft

- Send OH question guide to [narrator] to review: Before the interview recordings, it’s important that the narrator be able to review the question/topic guide to prepare their own journey down memory lane. This allows the narrator to feel comfortable and choose which intimate topics they would be willing to share or prefer to avoid throughout the recorded conversation.

- Schedule OH date(s): Since this oral history would cover 16 years across two separate artistic directors, we decided to schedule 1-1.5 hours per year. Each session picked up in a new year and then the final year session also included a reflection and looking-into-the-future review.

- 1. Bio + becoming involved

- 2. Practice within: YYYY + 1

- 3. Practice within: YYYY + 2

- n. Practice within: YYYY + Reflection/Rewind

- Send guidelines and requirements for remote OH : These resources can be helpful to prepare both the interviewer and narrator for the technical aspects of the oral history recording. This includes the physical location and room environment to be in, the recording devices, and backup recorders.

- If possible, please download a high-quality voice recorder app (for instance, the PCM Recorder Lite app or something similar) onto your smartphone. Have this ready to record your voice from your end. Record individual remote as backup (narrator and interviewer)

- Record narrator using Audio Recorder, backup (interviewer)

- Record audio and video on Zoom

The same notes document includes the script for a typical lede to begin each recording session. This is important to provide metadata for future listeners. The Question Guide is a point of reference to ensure topics are covered if/when lulls in the storytelling come up. It is important to remember that not all questions need to be addressed, and that it is more impactful to let the narrator share their story as it naturally comes out from their own memory space. The interviewer can pose questions to reroute the story to the preferred topic (i.e. the narrator’s experiences with the dance company) if the narrator deviates too far off topic. I also opened up the option for the narrator to add their own topics of discussion and/or edit the questions posed. This makes for a collaborative space between the narrator and interviewer, instead of the oral history practice being extractive and biased from the archival perspective.

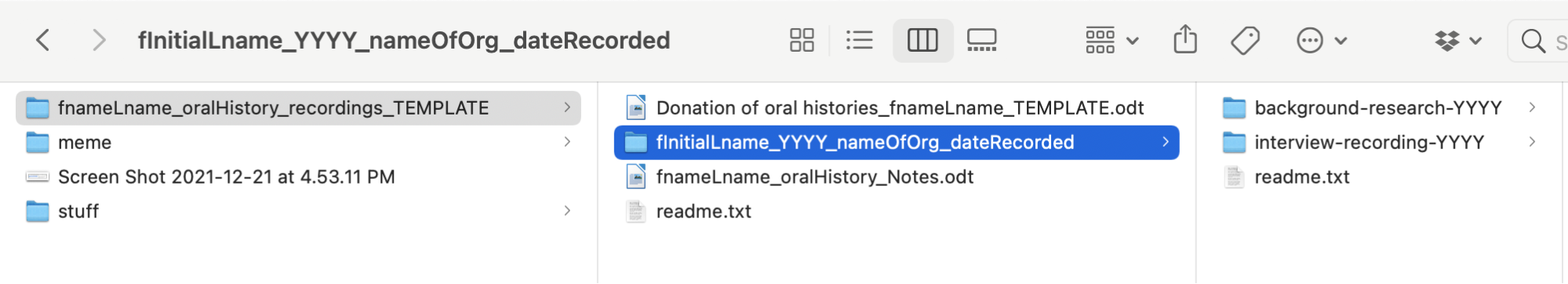

A screenshot of the folder hierarchy downloaded onto my personal desktop, highlighting the second-level folder, “fInitialLname_YYYY_nameOfOrg_dataRecorded”.

Next, there is the fInitialLname_YYYY_nameOfOrg_dateRecorded folder (Screenshot B). Each recording session covered one year of the narrator’s life with the dance company, where each second-level folder (e.g. in my case, one folder was JSmith_2008_AXIS_20200826) held all of the files related to that one year including the audio/visual recordings folder (interview-recording-YYYY), research documents (background-research-YYYY), and a readme.txt file where all research notes about and from the interviewer were documented (i.e. links, email threads between interviewer and narrator, etc.).

Pre-research and Web Archiving

Prior to each oral history recording, I duplicated the template folder. As I did research, I would record any notes, links, etc. into the readme.txt file. As I documented notes, I would imagine what type of contextual information would be helpful for a future archivist or researcher when they came upon this oral history folder in 2055. This is also where I noted any other questions or topics of discussion that I was interested in. The narrators, Judith and Marc, knew which year was to be discussed that week, so sometimes they would send over links to performances, rehearsals, interviews, press, images, etc. as they prepared to jog their memory about that year with AXIS. I saved this information in the readme.txt file and/or the background-research-YYYY folder if there were multimedia assets that were not already hosted on the cloud and needed to be saved locally.

As an aside, I also integrated a lightweight web archiving workflow during the research process. As I received links for the narrators or searched news sites, databases, theater and performance websites, etc. for information about the dance company and the narrator during a particular year, I often stumbled upon early internet websites that were at risk of digital decay or link rot. I added on the most lightweight, albeit still somewhat time intensive, series of web archiving steps that I could think of. This started the grassroots approach to archiving all of the online instances of AXIS and their Artistic Directors. This workflow relied heavily on Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine, and a more detailed account on how to do this is documented in section 3.3 Archiving online/web records of the Records Management Manual: re-organizing AXIS Dance Company’s files.

Recordings and Transcripts

In this post, I will not go into detail about the entire process of conducting an oral history interview since I believe the existing resources from New York Public Library for the Performing Arts Dance Oral History Project and Columbia Center for Oral History Research are robust and helpful enough. I do recommend taking those resources with a grain of salt and feeling free to adapt the practice to what works for you as a narrator and interviewer. Each community and memory-making process requires consideration of cultural and lived experience and I fully support reimagining new ways that oral history traditions can be practiced. For example, some oral history practices recommend recording audio only, but with the advancements of modern technology, video and audio recording has become more affordable and the power of seeing embodiment of the oral history session can open up many more opportunities to understand the human intentions and experiences through the narrator’s storytelling. Professor Jeff Friedman’s work on the influence that oral histories have on time consciousness and embodied communication are of note, particularly for dancers who might be rooted in more visual, embodied, and aesthetic forms of information transmission.

For my sessions with Judith and Marc, we met on Zoom since it provided audio and visual recording, and automated transcripts for reference. I set my Zoom account settings to record on the cloud, record both gallery and speaker views, and generate a transcript once the Zoom meeting session closed. This made the process of saving recordings and having access to a rough transcript much easier after learning about the fascinating lives of each artist. To sustainably cover the 16 years of AXIS considering our mental, physical, and emotional health, I met Judy and Marc separately once per week to interview about one year a week. This allowed us time to research for the following year and reflect on the memory-making each session required. Looking back over 16 years means revisiting the range of pleasure and struggles in life, so I was also intentional to allot 15-30 minutes before and/or after each interview to check in with each narrator. These check-ins allowed us to regroup as humans, not as archivist, interviewer, director, dancer, or narrator, but just to ensure that each of us were finding peace and rest before and after these oral history sessions—particularly important during the beginning of the first global pandemic since 1918.

Coda

The culmination of the oral history recording series wrapped up with the interviewer, me, editing the transcripts for accuracy in word recognition, grammar, etc. This is a very labor intensive process—especially with more than 17 hours of storytelling. Luckily, a friend gave me access to their Trint (audio transcription software) account so that I could regenerate transcripts from the Zoom-generated recordings. For reference, as of 2021, Trint’s automated transcription service is much more accurate than Zoom’s otter.ai software. This saved me time and energy as I edited each transcript.

After each transcript was done, I sent the transcripts to each narrator for them to review. In this stage of the oral history process, the narrator can review for accuracy, add footnotes for context on certain sections, and choose to redact any sections of their storytelling. I enjoy this process since it gives the narrator power to choose what will be preserved about themselves and their perspectives on the dance-making and performing processes, instead of the archivist or institution shaping the story from an outsider’s lens.

This last phase takes time and is still in process. Once all oral history transcripts are reviewed and edited, I will send these artifacts to Salazar at Bancroft Library for long term preservation and access at the Disability Rights and Independent Living Movement Archives. Currently, Smith’s first oral history and several artifacts from AXIS are available in the archives, and I look forward to contributing these robust oral histories to the archives for future listeners, researchers, dancers, activists, and physically integrated artists.

Please feel free to reach out to me if you have any questions, thoughts, and/or comments about this process. (Email Dance/USA’s Director of Archiving and Preservation Imogen Smith or Archiving Specialist Hallie Chametzky if you would like to be in touch.) I’m happy to chat with any dancers, arts administrators, and others who are interested in conducting oral histories to document and remember their creative works.

Images courtesy of Sarah Nguyễn and AXIS Dance Company.

Sarah Nguyễn is a librarian-archivist in training and a movement practitioner. Their research interests include the ephemerality of dance, the obsolescence rate of digital creations, and the processes and ethics behind preservation, reproduction, and representation. As an advocate for open, accessible, and secure technologies, Sarah has fulfilled these values through projects such as Preserve This Podcast, Investigating & Archiving the Scholarly Git Experience, Mark Morris Dance Group Archive, CUNY City Tech Open Education Resources, and linkRot, an intermedia performance simulating the physical euphoria that internet content creation permits into the digital decay that comes with/out feelings of loss.

Sarah Nguyễn is a librarian-archivist in training and a movement practitioner. Their research interests include the ephemerality of dance, the obsolescence rate of digital creations, and the processes and ethics behind preservation, reproduction, and representation. As an advocate for open, accessible, and secure technologies, Sarah has fulfilled these values through projects such as Preserve This Podcast, Investigating & Archiving the Scholarly Git Experience, Mark Morris Dance Group Archive, CUNY City Tech Open Education Resources, and linkRot, an intermedia performance simulating the physical euphoria that internet content creation permits into the digital decay that comes with/out feelings of loss.

With AXIS Dance Company, Sarah is looking forward to bringing physically integrated dance, disability rights, and independent living movements to our cultural heritage legacy. The North Bay Area is Sarah’s hometown and they are excited to bridge recent experiences in archival practices with their lifelong dance practice to the community that inspired them to pursue dance preservation. Currently, Sarah is a PhD student at the University of Washington.

____

We accept submissions on topics relevant to the field: advocacy, artistic issues, arts policy, community building, development, employment, engagement, touring, and other topics that deal with the business of dance. We cannot publish criticism, single-company season announcements, and single-company or single artist profiles. Additionally, we welcome feedback on articles. If you have a topic that you would like to see addressed or feedback, please contact communications@danceusa.org.

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed in guest posts do not necessarily represent the viewpoints of Dance/USA.