Benefits, Logistics and Costs

By Steve Sucato

Hubbard Street 2 Dancers Jade Hooper, left, and Elliot Hammans; photo by Todd Rosenberg, courtesy of Hubbard Street Dance Chicago.

Second companies are nothing new in dance. Some, like Ailey II and Hubbard Street Dance Chicago’s HS2, have been around for decades while others like Joffrey II have long gone by the wayside. In recent years, however, more and more dance organizations are seeing the value of adding a second unit to bolster their dancer ranks as well as provide an invaluable learning experience for talented young dancers to bridge the gap between student and professional.

Like their professional counterparts, second companies can come in a variety of shapes and sizes with varying goals and missions. To take a closer look at what makes a second company tick, five dance organizations with old and new second companies — BalletMet, Boston Ballet, Houston Ballet, Hubbard Street Dance Chicago, and Kansas City Ballet — weighed in about the benefits, costs, logistics, and concerns involved with starting and maintaining one.

“One thing we have to understand is that what one company calls a second company, another calls something else,” says Boston Ballet artistic director Mikko Nissinen. “San Francisco Ballet apprentices are like our second company [Boston Ballet II] and our trainees are like Houston Ballet’s second company. It’s a little confusing.”

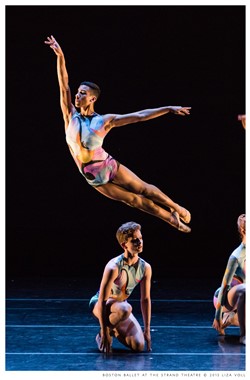

Boston Ballet II’s Desean Taber and Boston Ballet’s Albert Gordon in Viktor Plotnikov’s Colloquial Dreams; photo by Liza Voll, courtesy of Boston Ballet.

Whatever the moniker, “second company,” “studio company,” or some other variation, dance organizations give several common reasons for having one.

Education Through Performance

One main reason to build a second performing troupe is to provide talented young dancers, not quite ready for a main company contract, a place to hone their stagecraft and learn what it is like to be a professional dancer. Typically those dancers fall between the ages of 18 and 22. Some can be as young as 16, or as old as 24 if joining from a college dance program.

“The most important thing in bringing out greatness in a dancer is to put them on stage and put them on stage often,” says Hubbard Street 2 (HS2) director Terence Marling. “This … alters a person’s dancing more than anything that happens in the studio.”

In most second companies dancers augment the main company in corps de ballet roles. “A long time ago ballet companies hired inexperienced young dancers and after a few years they became well-functioning company members,” says Nissinen. “Today financial resources are so tight that nobody can afford to do that anymore, not even in Europe. So everybody needs dancers who are ready to dance. When they come from a school, they naturally don’t have professional experience and the likelihood they will survive in a company is less. If they go through a second company program, whether it is one year or two, they actually get all that experience and then when they join the company, they excel versus just get in.”

Kansas City Ballet artistic director Devon Carney, whose career began in the late 1970s as a member of Boston Ballet II (BBII), knows what being in a second company can mean to a young dancer. “It’s an invaluable internship to work in a professional company environment for a young dancer who has the ability but doesn’t have the experience yet,” says Carney.

Houston Ballet II (HB II) fields one of the largest and most successful second-company programs in the country, giving its 12 to 16 dancers from all over the globe the opportunity perform locally, regionally and nationally. They have even toured internationally to Canada, China, Hungary, Mexico and Switzerland. Houston Ballet artistic director Stanton Welch says he patterned the program after The Dancers Company, Australian Ballet’s second troupe, which his mother created when she was artistic director. “I gained so much both as a dancer and choreographer through that company that I wanted to have the same for us in Houston.”

Houston Ballet II in A Dance in the Garden of Mirth

Dance organizations with second company dancers performing main company corps roles also benefit because it gives more opportunities for main company dancers to do soloist and principal roles says Carney. This “trickle up” effect is good for the entire company, allowing more dancers more opportunities to dance better roles and the added dancers can also allow the main company to do larger ballets.

In the case of HS2, which is essentially a second professional troupe with its own touring schedule, their dancers can be called up to the main company when needed, much like a farm club to a Major League Baseball team or the NBA’s D-league.

While in practice second company dancers are a source of cheap labor, all those I spoke to were adamant they not be treated as such, especially to the detriment of their careers. To that end, all those artistic directors I talked to limit the time a dancer can spend in their organization’s second company to one to two years. That time limit benefits both the dancer and the organization.

After one to three years, if a director will not offer a second company dancer a main company contract, “It is important to push them out of the nest,” says BalletMet artistic director Edwaard Liang. “We don’t want to them to feel complacent in a company they cannot stay in forever. It is crucial around age 21 or 22 that they go out and find a job.”

An additional benefit of the dancer turnover for the organization is it allows opportunities for other talented young dancers looking to join the second company.

Some organizations like BalletMet build in another safeguard against the unfair use of their second company dancers. If they are used in a main company leading role more than once, they automatically receive a first-year main company dancer contract.

Outreach

Another reason dance organizations form second companies is to handle their community outreach activities. Carney had that in mind in forming KCB II as one of his first initiatives when he took over Kansas City Ballet’s leadership in 2013. The six-member KCB II is patterned after what Carney learned when he helped set up Cincinnati Ballet’s second company, CBII.

“Seeing talented young dancers in corps roles with the main company and in outreach performances where they get to do soloist parts, gives you a chance to get to know and evaluate each dancer,” says Carney.

Many of those I talked to place jurisdiction over their second unit under their affiliated dance academy because of the amount of lecture/outreach they perform for the organization. That outreach can come in the form of performing at local schools, assisted-care facilities, festivals, corporate events, and cultural institutions. Liang says BalletMet 2 charges schools a modest fee to perform. For performances at corporations, Liang says the company often exchanges performances for the opportunity to sell subscriptions and discounted tickets for the main company’s season to employees of the corporation.

BalletMet 2; photo by Jennifer Zmuda, courtesy of BalletMet.

HS2 also supports the education department of Hubbard Street with their outreach programs that Marling says, “seek to demystify the process of dance making and get kids dancing.”

When second company dancers perform in any capacity, they learn and grow as artists. For the organization it is also a chance to really evaluate them as performing dancers.

“The ballet staff and I, as well as many of the choreographers that come in, all have the chance to work with these kids,” says Welch. “So by the time they get into the main company, it is a continuation of the relationship as opposed to meeting someone new.”

That philosophy has meant higher matriculation numbers of dancers from second companies receiving main company contracts. To date, 12 members of HS2 have advanced to Hubbard Street’s main company, 35 percent of Boston Ballet’s dancers have come from BBII, and 70 percent of Houston Ballet’s dancers have come from HB II. Across the board, those numbers continue to grow.

For those who don’t land a main company contract, having second company experience on their resume can help in landing a contract elsewhere. Company directors interviewed report a high percentage (in some cases greater than 90 percent) of their second company dancers getting jobs with other dance companies.

To Tour or Not To Tour

While not as contentious as a Shakespearean drama, opinions differ on the use of a second company as a full-fledged, independent touring entity. Some, like BalletMet’s Liang, see having BalletMet 2 book its own independent mainstage productions as creating a competing partner within its own organization. Others like Welch disagree.

“We’ve talked about that,” says Welch. “Predominately we look at the venue and the city. In America right now HB II is really only touring to places that are too small for our main company to go. If the main company were to tour, it would be hard to justify going to those smaller cities. The second company can travel lighter and cheaper and they don’t have sets, lighting, union costs or orchestra [they use recorded music]. I haven’t felt like we have competed; if anything we have led one to the other.”

HB II is more the exception to the rule when it comes to ballet second companies touring. It’s more common for contemporary dance organizations like HS2 and Ailey II to embrace their second units as independent touring troupes that bring revenue into the organization while spreading the organization’s brand to more areas that perhaps can’t support or afford the full company.

Marling says HS2 functions like the main company in that it acquires works and performs them. It is a model that helps prepare HS2 dancers for what they will be doing if accepted into the main company. And if the main company is too big or expensive for a tour stop, HS2 can fill that need.

For others like BBII, scheduling keeps them busy with main company story ballets and outreach programming, leaving little time to tour. Finances are also a limiting factor says Kansas City Ballet’s Carney: “I think it would be great to get KCB II out on tour. We would certainly be out there hitting the colleges. We are just not there yet in our development.”

Repertory

The majority of the ballet second companies favor a mix of classical works and repertory works, either pulled from the main company or created especially for the second company. HS2’s repertory largely consists of works created on it, because part of its mission is to also identify and nurture young choreographers. To do so, HS2 initiated the International Commissioning Project (formerly known as the National Choreographic Competition) in 1999. Each year, the ICP provides residencies for chosen choreographers to create original works on HS2’s dancers.

Whatever they perform, Liang says it’s key the second company dancers feel a sense of ownership for their own repertory.

Auditions

Those I talked to paint a similar picture when it comes to filling its second company ranks. They get them from their affiliated dance academy’s upper level students (Nissinen says about 40 percent of second company members come from Boston Ballet’s school), summer course auditions, company auditions and video auditions.

Expense Report

Creating and maintaining a second company has its costs. Beyond paying dancer salaries, numerous other costs arise that a dance organization needs to take into account before forging ahead to start a second company. Some of the most important include:

- Dancer stipend/salary — Depending on the dance organization’s budget and the cost of living in a particular area, second company stipends/salaries can range greatly. For the 2015-16 season, Kansas City Ballet II dancers received a stipend $150/week, while BalletMet 2 dancers received $225/week. Hubbard Street 2 dancers received a base contract of 33 weeks at $425/week. On the other side, Boston Ballet II’s dancers received $600+/week or roughly 50 percent of the rate a first-year Boston Ballet corps de ballet dancer made during the 2015-16 season.

In addition to paying their dancers a stipend or salary, most organizations offer second company dancers other forms of compensation, including unlimited free classes at their affiliated dance academies (if they have one), access to physical therapy (if offered to the main company) and, in rarer instances, paid health insurance (Boston Ballet II) and housing assistance (Houston Ballet II).

Houston Ballet artistic director Stanton Welch calculates altogether the organization spends roughly $25,000 each year on each second company dancer.

- Footwear — Full coverage for pointe shoes and other dancer footwear can be a significant expense. “If you are going to start a second company, you have to face the reality that you really do need to cover their pointe shoes,” says Kansas City Ballet artistic director Devon Carney. “It is for their safety as well. Otherwise kids are going to stretch them out as long as they can and that can possibly lead to foot injuries.”

- Logo-wear/Uniforms — Because most second companies are part of an organization’s outreach efforts, most feel it important that the dancers are identifiable out in public as belonging to their organization through the wearing of company logo-wear. Typically that means providing second company dancers with uniform apparel and outerwear, which they can wear when representing the organization.

- Additional Wardrobe Expenses — Whether costuming a second company dancer for that troupe’s performances or for roles they perform in main company productions, additional personnel and labor hours have to be factored into a second company’s budget.

- Dressing Areas — Extra dancers mean extra space is needed for them to dress. That can lead to remodeling costs, new lockers, mirrors, etc.

- Transportation — Reliable transportation, such as a van with room for all the dancers, costumes and marley flooring, is necessary for the second company to get to and fro to performances and outreach events. An insured driver on the organization’s insurance policy adds another expense.

- Staff — While many second companies share staff with the main company in terms of ballet masters, marketing, finance and the like, more often than not a staff position needs to be added to oversee the second company. Typically that person wears the hats of administrator, teacher, rehearsal director, and sometimes choreographer.

Advice

For many young dancers being in a second company is their first experience living on their own: learning to cook and do laundry, manage finances, as well as learning what it takes to be a professional dancer. For a dance organization, that can translate to a unique set of problems more akin to parenting than a standard work relationship says BalletMet’s Liang. “It is almost like having children, sometimes they act out. They are in that in-between time, moving from being a student to a professional and that can be frustrating for an artist.”

Here are some points that may help an organization’s second company experience go smoother:

Know Why — If you are going to start a second company, everyone in the organization needs to know why it exists. “They need to understand the mission of the company,” says Hubbard Street 2 director Terence Marling. “There needs to be agreement between the organization and the second company director as to the function the company is meant to fill. It should be something that not only leads to greater success for the organization, but for the individual second company dancers.”

Hire a Director — Many companies pull from their existing staff to take on the management of the second company in addition to another job within the organization. Kansas City Ballet artistic director Devon Carney doesn’t recommend that. “Have a separate person that can take care of the company on a day-to-day basis. That person needs to be someone who can work at least 30 hours on the logistics of the second company and their performances, rehearsals, and the welfare of the young dancers. The additional expense is well worth it.”

Set Expectations Early — Let dancers and staff know what is expected of them from the start. If someone is not turning into a better dancer every day, then you are wasting their time. Even if they don’t get a main company contract with your organization, if your staff has done its job right, hopefully those dancers are set up to get a job with another company.

Be Generous with Dancer Stipends — As best as your organization can invest in your dancers, it may pay off in the long run. If dancers are not able to pay their bills and put food on the table, you are putting them into a very stressful situation.

Think About Separate Dressing Areas — Carney says he has learned over the years that main company dancers don’t want second company dancers in their space. “They consider them part of the school,” says Carney. “If possible assign them their own dressing area. That also acts as an incentive for second company members: knowing that when they become a full company member they get to move into the company dressing room.”

Stay On Top of Social Media — Social media can play a big role in your second company dancers’ lives and in doing so create some big headaches for your organization if left unchecked. “You are always morphing to keep up with changes in young dancers’ lives,” says Houston Ballet artistic director Welch. “How do you control copyright issues concerning choreographers, musicians and costume designers when someone can post photos and videos from the studio using their phone? Social media is the frontier that will change everything in the coming years. You need to look at how to contain that.”

Reach Out for Help — If you are thinking about adding a second company or have just done so, reaching out to other organizations via Dance/USA and other sources can offer a wealth of information. From administrative costs to arranging host-family housing, organizations that have already been there can help guide company directors and boards as they embark on creating second companies so they avoid mistakes and determine what is the appropriate next step for their organizations.

A former dancer turned writer/critic living in Ohio, Steve Sucato studied ballet and modern dance at the Erie Civic Ballet (Erie, Pa.) and at Pennsylvania State University. He has performed numerous contemporary and classical works sharing the stage with noted dancers Robert LaFosse, Antonia Franceschi, Joseph Duell, Sandra Brown, and Mikhail Baryshnikov. His writing credits include articles and reviews on dance and the arts for The Plain Dealer (Cleveland, Ohio), The Buffalo News, Erie Times-News (Erie, Pa.), Pittsburgh City Paper as well as magazines Pointe, Dance Studio Life, Dance Magazine, Dance International, Dance Teacher, Stage Directions, Dance Retailer News, Dancer and webzines Balletco, DanceTabs, Ballet-Dance Magazine/Critical Dance, and Exploredance.com, where he is currently associate editor. Steve is a chairman emeritus of the Dance Critics Association, an international association of dance journalists.

____

We accept submissions on topics relevant to the field: advocacy, artistic issues, arts policy, community building, development, employment, engagement, touring, and other topics that deal with the business of dance. We cannot publish criticism, single-company season announcements, and single-company or single artist profiles. Additionally, we welcome feedback on articles. If you have a topic that you would like to see addressed or feedback, please contact communications@danceusa.org.

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed in guest posts do not necessarily represent the viewpoints of Dance/USA.